Superstition and the Fisherman

The collection of superstitions which follows is not seen, in any way, as definitive. It simply records a number of the more commonly held beliefs once current in East Anglian fishing communities. Not all of them were peculiar to fishermen only; some had (and may still have) currency among seafarers in general, while others can be traced well inland. But no matter how extensive their area of circulation, all of them are interesting for what they tell us of the human mind and the way it works when faced with natural powers beyond either its understanding or its control.

The last factor is crucial when considering superstition of any kind. How does anyone explain the inexplicable? – with truth on very rare occasions, and with plausible mumbo-jumbo the rest of the time. Those of us living today have the benefit of the scientific discovery of the last hundred years particularly, but what about people living in times when fewer explanations were available? Take the case of a thunderstorm. How many contemporary British citizens could explain exactly what happens to cause one? And even if the physics are understood, does that in any sense diminish the awesome power unleashed during a tempest?

The forces of nature are always at their most imposing when at their angriest, and probably no one sees this more often and more directly than the seafarer. The closeness of contact with the elements not only breeds respect for the sea; it also makes a person look constantly for signs of adverse conditions, even perhaps when they are not present. Such a sense of foreboding is undoubtedly the origin of some of the superstitions recorded below. They are, if we like to think of them in this manner, omens of what could happen rather than what had – but that in no way diminishes their hold on people.

If anything, the opposite is true. Most of us have something deep within us which responds to the mysterious, or even (on occasions) the obviously occult. Rationality plays no part in the feelings; it is something that is there within us – a legacy from our primitive past, which centuries of progress and improvement have not succeeded in eradicating. Thus it is that none of us should have too much trouble in following the line of thought that produced these superstitions, several of which function on the principle of sympathetic magic, where an action or deed can assume a good or evil outcome simply by association or analogy.

1. Breaking eggshells. This was always done after the cracking of eggs in cooking, because it was believed that half an eggshell could provide a witch or an evil spirit with a craft in which to put to sea and there cause havoc. Similarly, after a boiled egg had been eaten, the shell was either broken or turned upside-down in the egg-cup and a hole poked through it. The writer was taught the latter practice, as a very small boy, by his grandparents – and this was well inland, in a Norfolk village situated between Bungay and Harleston.

2. Never launch a vessel on a Friday. This custom was always strictly adhered to with newly built craft. Nor was a fishing-boat’s keel ever laid down on a Friday. Both practices were believed to bring bad luck, even to the point of total loss of both vessel and crew. The taboos surrounding Friday probably have their origin in pre-Reformation times, when Friday was held sacred as the day on which Jesus Christ died.

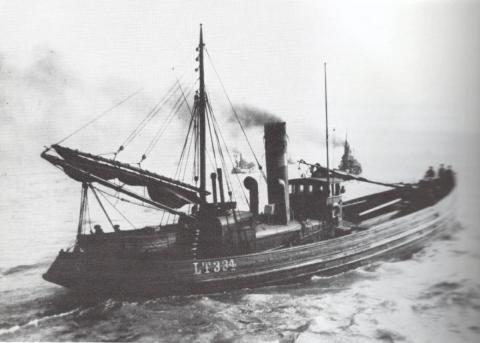

3. Never begin a fishing voyage on a Friday. Another of the common superstitions regarding Friday. What is meant specifically here by “voyage” is a major fishing time-of-year, such as the local autumn herring season, or the winter migration of East Anglian crews round to Newlyn to catch mackerel. Once the “voyage” was under way, there was no threat in boats leaving port on a Friday because they were now making “trips” – and that was completely different matter.

4. Women on board ship. This was anathema to most fishermen – one of things they thought most likely to cause a vessel to sink. The idea of women representing a destructive force is to be found the whole world over – a reversal, really, of their biological creativity and with undertones of the male feeling sexually threatened by them. It is no accident that the old stories have Eve plucking the fruit and Pandora opening the box.

5. Washing clothes. This was never done on the day that a fisherman left home to start a voyage. To do so would undoubtedly prove fatal and cause the man to drown, the domestic task being synonymous with “washing his life away” – a good example of sympathetic magic in operation.

6. Watching a loved one depart. This simple action was fraught with danger if the wife or children watched the man of the house, or any other relative, disappear from sight at the end of the street, or round a corner, when starting off on a fishing voyage. It meant that he would never be seen again. The remedy was simple: you did not stand and watch him for any length of time after the goodbyes had been said.

7. Dislike of clergymen. Many local fishermen believed that to allow a minister of religion to step on board was bound to bring bad luck. This was not so much to do with losing the vessel itself as with causing poor catches to be had. The Bishop of Aberdeen caused an upset on the Lowestoft fish-market in the post-war period when he attempted to set foot on one of the local boats, in ignorance of local beliefs (Scottish fishermen did not share these, to the same degree). A notable exception to the rule was the Rev. A. D. Tupper-Carey, rector of St. Margaret’s, Lowestoft, in the Edwardian era. He was so well thought of among the fishermen that he was welcome aboard any time, and he even sailed down to Shetland on board one of the steam drifters during the early 1900s for the summer herring voyage.

8. Dislike of nuns. Female clergy roused even stronger feelings than ordained ministers, combining both the traditional dislike of women and the suspicion felt towards people connected with organised religion. In fact, it wasn’t unknown for Lowestoft fishermen to refuse to put to sea if they passed, or saw, a nun on their way to the harbour. And there was a good chance of their doing so if they lived in the southern part of town, because St. Mary’s Convent stood at the top of Kirkley Cliff. The only remedy, apparently, for warding off the ill luck caused by sighting a nun was to immediately touch some object made of iron. This was accompanied by the shout of “Cold iron!” or “Iron! Iron!”. And if there were no gates, lamp-posts or fence railings conveniently to hand, the studs in the soles of boots would suffice. This belief in the efficacy of iron to counter a malign influence goes back to the Anglo-Saxon period at least, and may be even older.

9. Copper coins in fishing-net corks. It was not unusual for the corks on drift-net headlines to be split at periodic intervals and have pennies or halfpennies inserted into the incisions. This served a dual purpose: the coins acted as weights along the headline, but they also functioned as good-luck charms in the sense of being an offering to the gods in exchange for a good catch.

10. Wetting the nets. Before a herring voyage commenced, many boatowners used to have a small celebration in the yards of their net-stores. The success of the voyage was toasted in either beer or spirits, and a few drops of the particular beverage were sprinkled on the nets. Such a libation is both ancient in origin and thoroughly pagan.

11. The number of drift-nets cast. This was always an odd number, whether fishing for herring or mackerel, the reasoning being that “the extra net” would bring good luck. Hence, a drifter would shoot 75 nets, or 83, or 111 etc., depending on its size and fishing capacity.

12. Buying a catch. Religious feeling (or perhaps it would be more accurate to say pseudo-religious) manifested itself on board ship in the custom of throwing some pennies or halfpennies overboard before shooting drift-nets or trawls. This was ostensibly to “buy a catch” from The Almighty, working on the principle that nobody ever gets something for nothing.

13. “Over for the Lord”. This was commonly uttered (there were several variations of it) by skippers and crew members on both sailing drifters and steam craft prior to the first net being cast. It was a prayer, really, for a good catch of herrings and it is said to derive from references in the Gospels to the hauls of fish made by certain of the disciples in the Sea of Galilee (Matthew 4. 18-19; Mark 1. 16-17; Luke 5. 5-7 and John 21. 4-6) – particularly the one mentioned in the last of these, which is generally referred to as “the miraculous draught”.

14. Abusing the Almighty. In the event of trawls or drift-nets coming up empty, it was not unknown for some of the more blasphemous skippers to blame the Creator, whom they held directly responsible for their bad fortune, and invite him to come down and give an account of his actions. Some even used to go as far as to challenge him to a fight, in which (should he appear) he might expect to suffer some degree of bodily harm.

15. The King Herring. Occasionally, an Allis shad (Alosa alosa) would be shaken from the meshes of drift nets as they were being hauled. Because of its passing resemblance to the herring, and its larger size, it was always identified as a “shoal leader” and was therefore thrown back into the sea, to lead future shoals into the awaiting nets. The cry of “King Herring!” usually accompanied the act, not only to indicate the belief concerning the species, but to comment perhaps on the importance of herrings generally in the local economy.

16. The October full moon. Traditionally, East Anglian fishermen believed that the best catches of herring were taken at “October full”, especially when that occurred about the middle of the month (or even later). Landing statistics bear this out, but it had nothing to do with any gravitational influence. It just happens that the southward movement of the shoals towards their spawning grounds in the English Channel peaked at about this time, before gradually diminishing throughout the month of November.

17. Scrubbing the decks. Some of the more old-fashioned skippers did not believe in their boats being too clean, because they reckoned that a certain amount of fish refuse lying around showed that a vessel was earning money. Too great an insistence, therefore, on cleanliness might well take away the luck needed to make paying hauls.

18. Leaving deck-brooms on top of nets. This was never done, either on board ship or at the quayside, and the reason for this is a perfect example of sympathetic magic. If a fisherman were so foolish as to do such a thing, then he was inviting disaster next time the nets were cast. They would, in all likelihood, be lost, because leaving a broom lying on top of them represented their being swept away.

19. Leaving bunker-lids lying the wrong way up. The metal lids that were set into the deck above the coal bunkers and fish-hold were not unlike small metal manhole covers to look at. When they were taken out, they always had to be placed on their backs, which then symbolised the hull of the vessel. If they were left lying the other way up, it was believed that this might cause the boat to turn turtle.

20. Hatred of pigs. These animals had a bad reputation among fishermen because (it is said) of the story of the Gadarene swine in the Gospels (Mark 5. 11-13) . The specific reference as to how the herd ran into the waters and drowned is reputed to have made fishermen very uneasy, though no doubt the reputation of the pig as a “dirty animal” also played its part. Not only were crew members forbidden to mention pigs on board ship, some skippers also refused to carry bacon or pork among the boat’s provisions. Another possible explanation of the unease surrounding the animal may be traced back to Celtic times, when a powerful British earth-goddess, Ceridwen, is said to have taken the form of a large black sow as one of her manifestations. Whatever the case, there were exceptions to the rule of taboo where pigs were concerned – a notable one being the Lowestoft trawler skipper, William (“Oscar”) Pipes, during the 1930s. He had the wheelhouse of his vessel, the Blanche (H 928), decorated with dried and varnished pigs’ tails nailed around the top and with a head similarly treated set above the window. Such a flagrant disregard for tradition did not seem to have affected him unduly either, because he was a successful operator.

21. Dislike of other animals. While pigs attracted the greatest ill-feeling, animals in general were often taboo in conversation on board ship. Rabbits gave cause for unease among some fishermen; so did cattle, horses and sheep; and even exotic creatures such as monkeys, elephants and camels were frowned upon. When radio receiving-sets first began to be installed in the Lowestoft and Yarmouth fishing fleets during the 1920s and 30s, some of the skippers would switch them off as soon as they heard livestock market reports and the prices mentioned, for fear they might hear any forbidden animals referred to. In view of such feeling, it may seem strange that many vessels carried a cat (usually to control vermin) and that some skippers would often take their dogs to sea with them.

22. The “Fiddle-fish”. The monkfish, or angel ray (Squatina squatina), was given this name because its shape supposedly resembled that of a violin. It was the custom on the Lowestoft sailing smacks, if one of them was trawled up, to nail it by its tail to the mizzen mast as a good luck charm. Sometimes, the fish had a lashing secured to its tail and it would then be thrown overboard for the boat to tow along on the journey back to port.

23. Rats. Everyone has heard the saying, “Rats always desert a sinking ship”, and fishermen were no exception in believing this. Even so, the presence of these animals on board was something of a mixed blessing, so many drifters and trawlers carried a cat in order to keep the numbers down.

24. Whistling on board ship. This was strictly forbidden at sea, and even frowned upon in port, because it was believed to be a sure way of raising high winds and gales. Both the expulsion of air through the lips and the sound that this makes combine to create a perfect example of sympathetic magic at work.

25. Singing on board ship. This was disliked by some skippers, especially when at sea, because they thought that it would lead to poor catches. Herring fishermen particularly believed this.

26. Stirring tea with knives or forks. This might be done sometimes on board if a spoon wasn’t immediately to hand, but it was a practice disapproved of by the older fishermen in particular, who saw it as a potential cause of trouble among crew members. “Stir with a knife; stir up strife.” That was one saying. Another went thus: “Stir with a fork; stir up talk.” And talk, in this case, meant arguments.

27. The colour green. This was another of the fisherman’s great hates and a very bad omen indeed. Hence, no one wore green clothes of any kind on board ship and few boats were painted green. The superstition surrounding the colour is both ancient and widespread, for it is the so-called “fairy hue”, the Earth Mother’s own personal tint – and, in seeming to represent the substance of life itself, it has long been held in awe. George Ewart Evans, over many years of collecting the oral history of the East Anglian farmworker, frequently encountered unease concerning the colour green.

28. White-handled knives. These were taboo also as far as some of the older fishermen were concerned and, whether for eating meals or gutting fish, were not allowed on board. The particular belief at work here was the association of white with death – the idea of its being the “corpse colour”. One of the writer’s respondents (Jack Rose), who worked on a motorised smack during the early 1950s, was compelled to throw a bone-handled gutting knife overboard as the vessel left Lowestoft harbour, and it was accompanied by a green jumper knitted for him by his fiancée!

29. White stones. These were disliked by many fishermen for the reason explained above and, if any were trawled up from the seabed, they were quickly thrown back. It was not unknown for some of the old smack skippers (and owners) to pick through the shingle ballast of a new vessel and discard as many white stones as they were able to.

30. Ear-rings. It was believed that the piercing of ears and the wearing of ear-rings was able to improve eyesight. The usual custom was to have only the left lobe done and to wear a single, gold ring therein. The practice seems to have penetrated well inland; the writer’s maternal grandfather, a farmworker from the Acle area of Norfolk, always sported an ear-ring. He may well have had contemporaries, as a young man, who went fishing out of Great Yarmouth.

31. A baby’s caul. The membrane found on the heads of some new-born infants was regarded as a sovereign charm against drowning. High prices were paid for cauls, which were usually carried somewhere about the person – often in a small bag hung round the neck on a drawstring. The most famous caul recorded is that mentioned in the first chapter of David Copperfield. The eponymous hero was born with one, which was advertised in the newspapers for the sum of fifteen guineas and, having failed to attract interest, was then raffled off locally. Dickens would have become well acquainted with maritime belief and practice during his visit to Great Yarmouth in 1849 and he was a master at incorporating regional culture into his novels. He may even have known that the caul was valued so highly because of its passing resemblance to the shape of a boat’s hull. Here again, sympathetic magic is seen in operation: the analogy between the caul’s shape and the safety that represents to someone who possesses one while at sea.

32. Dying on the ebb tide. It was widely held in fishing communities that a dying person would hold on to life until the tide turned from the flood to the ebb. Then he or she would depart this world. Again, there is a reference to this in David Copperfield, chapter 30, where Mr. Peggotty describes Barkis’s passing to David (they are both present in the room, at his deathbed) in the following way: “He’s a-going out with the tide.”

33. Seagulls. These were believed to be the souls of drowned seafarers, which had assumed another form and could not leave the element that had caused their demise.

34. Fairy-loaves. These were fossilised sea urchins, which were sometimes found on cliff-faces and beaches. They were also known as “pharisee-loaves”, or “farcy-loaves”, and were regarded as symbols of good luck, often being taken into people’s houses, varnished over and placed on mantle-pieces and shelves. Their shape, being roughly suggestive of a loaf of bread, led to the idea that those people who possessed them would never starve. The word “pharisee” (and its corruption, “farcy”) derives originally from the Celtic fer-sidhean, which literally means “fairy-men”. George Ewart Evans has an illuminating piece about fairy-loaves in chapter 13 of The Pattern Under the Plough.

35. Hag-stones. Any stone with a hole through the middle has long been regarded as lucky, especially as a charm against the depredations of witches and evil spirits. Many fishing vessels had them hanging up in either cabin or wheelhouse, or above the entrance to these, just as one might have expected to find them hanging over the doorway of a house. Again, there are details of the practice in chapter 18 of the book cited immediately above.

36. The all-seeing eye. The oculus which is painted on the prow of many Mediterranean fishing craft was paralleled in East Anglian vessels of both the sail and steam eras by the ornamental hawse-pipe and accompanying maker’s scroll. The hawse-pipe was the hole through which the anchor chain ran and it usually had a red surround, as well as a blue, wooden tampion for insertion when it was not being used. The maker’s scroll was the particular shipbuilder’s individual device, which was cut into the bow of a boat on both the port and starboard sides and then gilded. It always incorporated the hawse-pipe and formed a most attractive motif. The painting of an eye-like image on the bows of craft goes back to the times of ancient Egypt, when the eye of Horus was one of the most potent of all good-luck charms. No local vessel in East Anglia was reckoned complete without its builder’s scroll, but it is debatable whether people at the time were aware of just how old a tradition was being continued.

A majority of the superstitions above were collected by the writer during a tape-recording programme carried out during 1976-83 with local people (thirty-seven men and seven women), with the intention of producing a sound archive to record an important part of the Lowestoft area’s industrial and maritime history. They form the basis of six published works: The Driftermen (Reading, 1978), The Trawlermen (Reading, 1979), Living From the Sea (Reading, 1982), Following the Fishing (Newton Abbot, 1987), Fishing Talk (Cromer, 2014) and The Last Haul (Lowestoft, 2020).

The original recordings (103 hours in all, on BASF C60 cassettes) – together with the original, handwritten transcripts – were gifted to the Suffolk Record Office in 2007 and form part of the County Oral History collection. The recordings have been digitised and the transcripts word-processed. Two photo-copied sets of the transcripts were made: one forming part of the Port of Lowestoft Research Society’s archives, the other being lodged at the University of Freiburg, in Germany, where it forms part of a bank of material for the advanced linguistic study of English regional dialects.

The transcripts were written in such a way as to reflect the local way of speaking, with spelling which represents the particular pronunciation of words and with grammatical forms which are (or were) commonly used. There was no attempt made to represent the dialect in full phonetic form, as this would have been time-consuming and have led to the transcripts being hard to read by non-specialists. On average, it took something like eight to ten hours to write up each hour-long interview. A small number of sessions were a half-hour only.

This article (minus the last three paragraphs) was previously published in Suffolk Review, New Series 71, Autumn 2018 - this being the twice-yearly journal of the Suffolk Local History Council. CREDIT:David Butcher

Add new comment